Recently in the news is a decision in a lawsuit regarding the potential eviction of a defrocked nun in a Russian Orthodox convent located in Nanuet, New York. This case is an interesting intersection of two areas of the law that our firm practices; namely, how the decisions of a religious organization can affect the disposition of real property, as well as the residents of said real property.

Recently in the news is a decision in a lawsuit regarding the potential eviction of a defrocked nun in a Russian Orthodox convent located in Nanuet, New York. This case is an interesting intersection of two areas of the law that our firm practices; namely, how the decisions of a religious organization can affect the disposition of real property, as well as the residents of said real property.

Prior blog posts have discussed how religious corporations must obtain approval from the New York State Attorney General in order to sell, lease, or mortgage real estate owned by the religious organization. This often causes disputes where there are different factions within the religious organization, and these factions cannot agree on whether to sell real estate in order to relocate the place of worship. As prior posts have discussed, courts are reluctant to intervene in disputes which are solely the result of disputes over religious doctrine. However, disputes over control of a religious organization which can be resolved on the basis of neutral principles, that is, without second-guessing decisions made solely on the basis of theological grounds, may be resolved by the court.

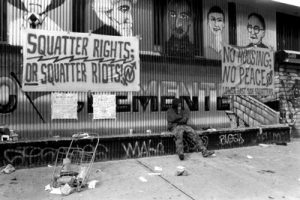

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution generally forbids government involvement in religious disputes. This principle also applies to the Courts, which are, in essence, instruments of the government, whether state or federal. The lawsuit under discussion involves attempts to allow an ejectment action against a nun who was defrocked by her parent religious organization, the Russian Orthodox Convent Novo-Diveevo. Our blog has previously discussed evictions against certain “non-traditional” tenants, such as licensees and invitees, who usually do not have written leases, but reside at certain properties. The usual course of action in such matters is to serve a Notice to Quit, giving the tenant (often referred to as a licensee or invitee, depending on the specific situation) thirty days in which to vacate the premises. If they do not vacate, the owner of the property can then either bring a petition for eviction in the local landlord-tenant court, or, in cases involving more complex issues, a civil action for ejectment in the Supreme Court in which the property is located.

New York Real Estate Lawyers Blog

New York Real Estate Lawyers Blog