A recent article in the New York Times discusses new legal developments relating to the Westchester County, New York fair housing settlement. For those who are unfamiliar with the situation, a lawsuit was brought in 2009 by a public interest group against Westchester County, alleging housing discrimination. In order to settle the lawsuit in 2009, then-County executive Andrew Spano agreed to build at least 750 units of “affordable housing” in Westchester by a Court-approved settlement agreement.

A recent article in the New York Times discusses new legal developments relating to the Westchester County, New York fair housing settlement. For those who are unfamiliar with the situation, a lawsuit was brought in 2009 by a public interest group against Westchester County, alleging housing discrimination. In order to settle the lawsuit in 2009, then-County executive Andrew Spano agreed to build at least 750 units of “affordable housing” in Westchester by a Court-approved settlement agreement.

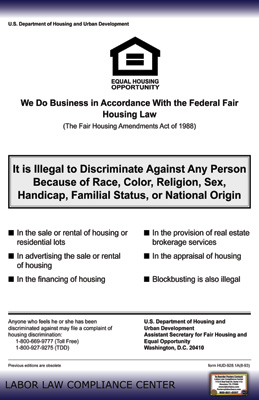

Recent developments in this case involve the federal government threatening to have the County held in contempt of Court for failing to comply with the settlement agreement. In addition, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development has stated that it will revoke $7.4 million in money awarded to Westchester County if the county does not comply with the terms of the settlement.

More specifically, the settlement agreement required that the county create 750 houses and apartments for moderate-income people in particular Westchester neighborhoods. The County has claimed it is actually ahead of schedule to accomplish this goal. The current County Executive states that the County already has financing for 305 units of affordable housing in place. However, HUD and the housing advocates who brought the original lawsuit claim that the County is not only obligated to build affordable housing, but also to take affirmative steps to prevent housing discrimination within Westchester under the terms of the settlement agreement.

One major lesson to be taken from this dispute is the necessity for exact and specific language to be written into any settlement agreement. If there is indeed language in the settlement agreement requiring Westchester to take steps to prevent discrimination in housing, that language may be so broad as to require almost any action that is deemed by the County’s opponents to be within the spirit of the agreement. The current County Executive, Rob Astorino, vetoed new legislation requiring landlords not to discriminate against tenants using Section 8 vouchers to pay their rent. Section 8 vouchers are in essence government-assisted payments given to low-income tenants. Mr. Astorino argued that he was within his rights as County Executive to veto legislation he deemed not in the best interests of the County. He also claimed that he was not bound by the terms of the settlement agreement, as he was not County Executive at the time that the settlement agreement was executed.

A Federal Appeals Court recently rejected both of these arguments. It ruled against the County and Mr. Astorino, stating that, under the terms of the settlement agreement, the County, and the County Executive, is required to promote legislation prohibiting discrimination in housing. The Court said that Mr. Astorino’s 2010 veto of legislation banning discrimination in housing based on source of income (such as Section 8 vouchers) was not in compliance with the terms of the settlement agreement. The United States Justice Department has now threatened to hold Westchester officials in contempt of Court if they fail to enact such legislation.

Of course, this continuing dispute could have been easily avoided at the time of the negotiation of the original settlement agreement. By agreeing to promote “fair housing” and take action to prevent discrimination in housing, the County accepted an open ended and ambiguous obligation which will now be subject to endless Court rulings and determinations, and which may never end. Instead, the County should have agreed to take certain specific actions which would not be subject to any legal interpretation. There would have then been no doubt as to the County’s exact obligations under such a settlement. The settlement also should have had a time limit within which the County was to perform these actions. By agreeing to “promote fair housing,” and not agreeing to a specific time period, the County has “opened the door” to having Courts and Judges decide what the County needs to do to promote fair housing, and the time period to perform such actions will almost certainly extend far beyond what the parties envisioned. If such an agreement could not have been made specific, the County should have continued to litigate the action and not settled under these conditions.

New York Real Estate Lawyers Blog

New York Real Estate Lawyers Blog